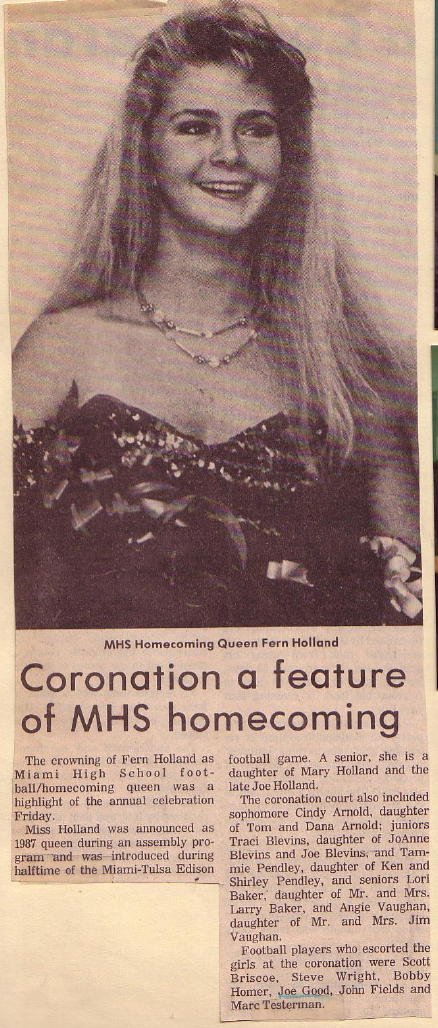

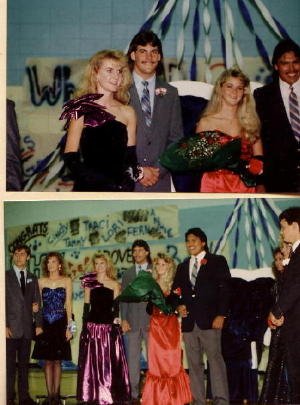

PHOTO GALLERY

SENIOR YEAR AT MIAMI HIGH SCHOOL

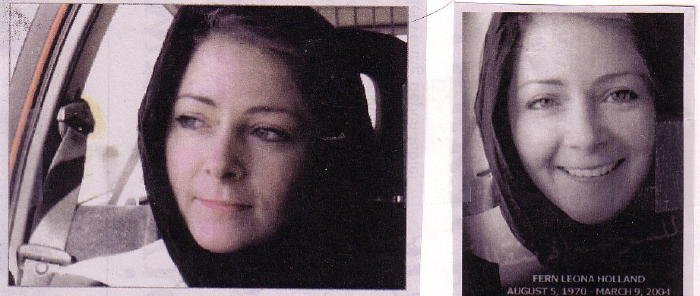

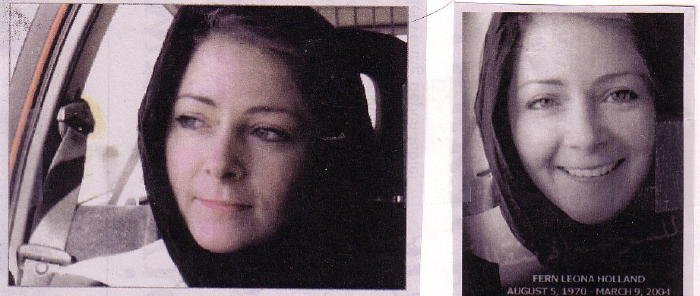

Fern Holland

Soldier of Human Rights

"I love the work and if I die, know that I'm doing preciselyl what I want to be doing - working to organize and educate human rights activists and women's groups-human rights and democracy education for independents who are motivated and capable of leading this country."

"Each time a man stands up for an ideal, or acts

to improve the lot of others, or strikes out against injustice, he sends

forth a tiny ripple of hope, and crossing each other from a million different

centers of energy and daring those ripples build a current which can sweep

down the mightiest wall of oppression and resistance." - Robert Kennedy.

This statement by Robert Kennedy could well have been the motto Fern lived by. After Fern's death, Vi Holland, Fern's sister, made it clear the media should not glorify Fern as a hero for some front page story or 10 second sound bite. Rather the media could help raise awareness of Fern's beliefs. Fern's beiefs were not unlike our nation's founding fathers'. She believed all people are created equal. Fern traveled to other nations spreading this belief, not through propaganda but through actions.

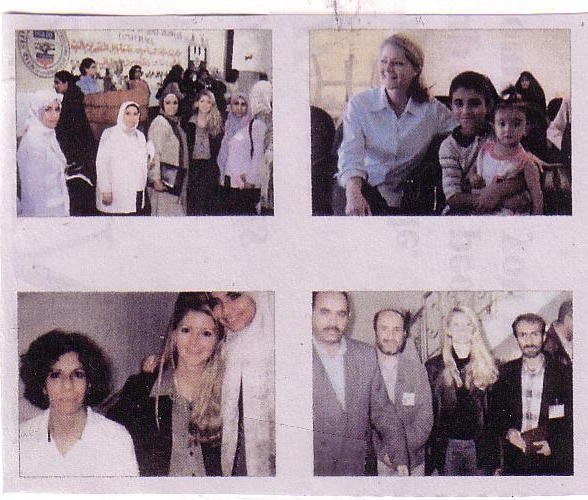

Fern was in Iraq as a member of the Coalition Provisional Authority. She investigated human rights violations, set up women's rights conferences and assisted with the new constitution. She and two others were killed when gunmen posing as Iraqi Police officers stopped her vehicle at a makeshift checkpoint near the town of Hillah, about 35 miles south of Baghdad.

Fern told friends her mother was her hero, but brother Joe Holland thinks it was the other way around. "Fern was my mother's hero. That's the truth," he said. Fern was in first grade when her parents went through a bitter divorce. Her mother moved from Bluejacket to Miami, taking Vi and Fern. The brothers stayed with their father. An older sister was already living on her own.

"My mother, she was troubled - hurt - by the divorce," Joe Holland said. "She needed somebody, she really did. I think Fern just knew that instinctively. She was there for her, day in and day out." Tending to her mother did not keep Holland from doing what other kids were doing - and usually besting them at it, her siblings said.

"She was the best athlete of all of us," another brother, James Holland, said. "Softball, basketball, skiing, she was good at everything."

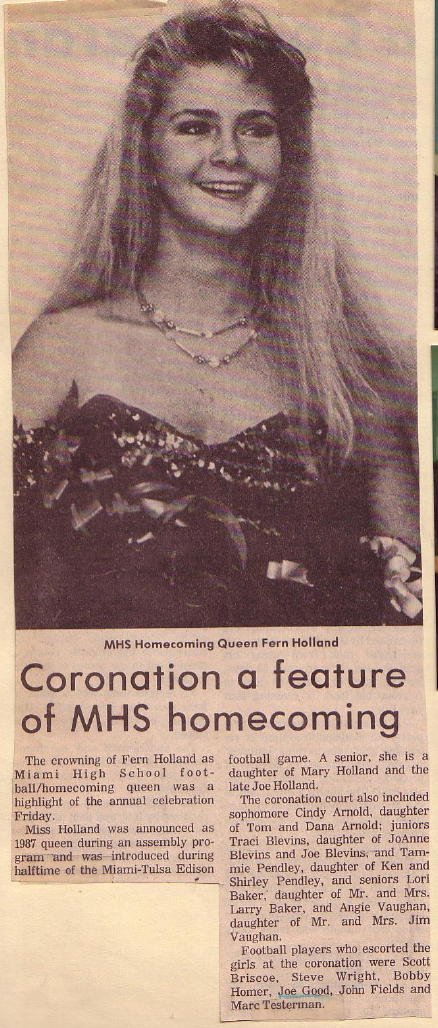

Grades were never a problem for Holland either. She graduated as salutatorian of her senior class. But she impressed her classmates in other ways as well. She served as class officer and school royalty her Junior and Senior years.

Chebon Porter, now a medical doctor in Birmingham, Ala., remembers Holland driving a black sports car down a Miami street, her hair blowing in the wind and the sound of Styx's "Come Sail Away" blaring out the T-top. "To a young man of the age, she was incredibly intimidating." he said.

When Holland graduated from OU with a psychology degree in 1992, she was debating whether to become a doctor or lawyer. Unable to choose, she spent the next year traveling. Harmon, her college roommate, said Holland tagged along with a friend going to Israel on an archaecological dig. After that, the two women traveled across Europe and into Russia.

Friend Marny Dunlap, an Oklahoma City pediatrician, said Holland did volunteer work in a Russian orphanage or hospital. "She told me she was mainly working with children who were Chernobyl victims," Dunlap said. "She talked a lot about seeing these kids and how much they touched her and how sick they were. I think that probably was when she made her decision" to go to law school instead of medical school, Dunlap said.

Not so, said Terry Todd, a Tulsa lawyer and famiy friend. He hired Holland as a low-level law clerk at Barkley & Rodolf when she returned from her travels. "She wasn't sure if she wanted medical or law school. I said, "Well, why don't you come to work for us? You might decide you don't want to be a lawyer," Todd said.

Instead, Holland enrolled in the University of Tulsa Law School and graduated near the top of her class. Barkley & Rodolf immediately promited their longtime law clerk to lawyer, and Holland spent three years there, buying a home in Tulsa and seeming to dig in to the world of medical malpractice defense, the firm's specialty. But Rodolf knew it would not last. "I never saw her as someone who would settle into the corporate life."

In 1999, the Conner & Winters law firm in Tulsa lured Holland away with the chance to practice environmental law. Jim Green, her boss there, said Holland never concealed her itch to move on. "We defended cases all over the eastern half of the state so we had a lot of windshield time together. She told me she had always wanted to do something with her life and with her law degree to work for human rights, particularly abroad," he said.

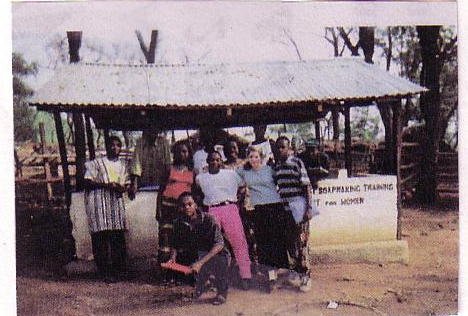

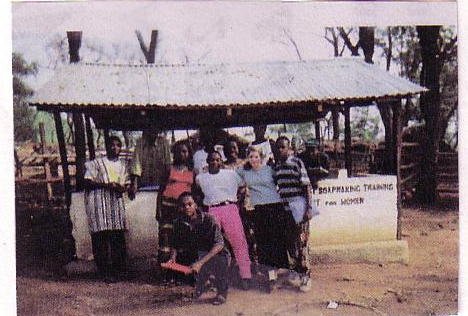

In the spring of 2000, Holland announced she had joined the Peace Corps and was going to Namibia in West Africa. "It's the happiest I'd ever seen her," said Todd, one of Holland's mentors at Barkley & Rodolf. Holland became a role model among the group of Peace Corps Volunteers who trained with her that summer.

Jessica Samuel, who now works on the Navajo Reservation in Arizona, said the others looked up to Holland. "She had what a lot of the younger people would envy as a ral life, a real job," Samuel said. "For her, the Peace Corps wasn't a stepping stone to a law career. It was an end goal. She talked a little about practicing law not being satisfying morally."

Holland learned the Oshikiyama dialect and then went to live in Onamutai, where her job was to get the community and parents involved in the village school.

"We were without running water," Samuel said, "Her family, I believe, had electricity, but many time the electricity would go out. It also got really hot. But she was fine with it. I think her only frustration was not having a vehicle; not being able to go from village to village to get things done."

Holland helped students who had never left the illage raise money for a trip to the national capital Windhoek, to meet their president. A local newspaper clipping tells the story but never mentions Holland.

Debbie Anderson, another Peace Corps volunteer, remembers Holland being unusually eager to talk to Namibians. "It was like she's seek out people to talk to and find out about their life situation, how they felt about things in their country, what their dreams were, how they thought things could be improved," Anderson said.

Holland came home after the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks - about eight months short of her two-year Peace Corps commitment. "We understood why, obviously," Anderson said. "She had already accomplished so much. She left for appropriate reasons.

"In a letter, Holland told Samuel, her need to go home was not based on fear for her personal safety, but on her memory of the terrorist bombing in Oklahoma City and the recent death of her mother. "She had a sense of urgency that she needed to get back home and be with her family," Samuel said.

In Oklahoma, Holland resumed her work with Conner & Winters, but not for long. By January she had been accepted into the prestigious Georgetown Law Center in Washington to pursue an advanced degree in international law.

In Washington, Holland joined another law firm, where she worked on and off in 2002 and 2003. But her studies kept getting shoved to the sidelines. She had not even finished her first semester when she agreed in April to go to Guinea for the American Refugee Committee. The committee wanted her to invstigate alleged human rights abuses at a refugee camp.

"I told her, 'Fern, you're working on your LLM (degree). You can't just leave mid-semester and go to Africa" Green remembers saying. "She told me, 'Well you can if somebody needs you."

Colleen Striegel of the American Refugee Committee accompanied Holland to Guinea on a 10-day fact finding mission. Afterward, Holland wrote a report that said women were being sexually exploited at the camp. She recommended establishing a legal clinic to help them seek justice. The committee hired Holland to go back to Guinea and start the clinic, Striegel said.

"It was really groundbreaking work she ended up doing. People thought it couldn't be done because this is Africa, this is a refugee camp," Striegel said.

At the time of Holland's death, the clinic had handled 118 cases including rapes, sexual assaults, wife beatings, family abandonment and sexual exploitation, according to a tribute from the Guinean refugees read at Holland's memorial service.

"Let it be known that your name and memory have gone into the annals of history forever," the grateful refugees wrote.

Vi Holland said her sister had a dream of opening legal clinics like the one in Guinea in refugee camps worldwide. Instead, the U. S. Agency for International Development hired her to work for women's rights in Iraq.

Leah Werchick of USAID said Holland's trip from the United States to Al Hillah, where she was based was a disaster. Misplaced uggage, delayed flights. "By the time she finally made it to Al Hillah, you's think she'd be exhausted. But she was just chomping at the bit, ready to start work right then," said Werchick, who had gone ahead to set things up.

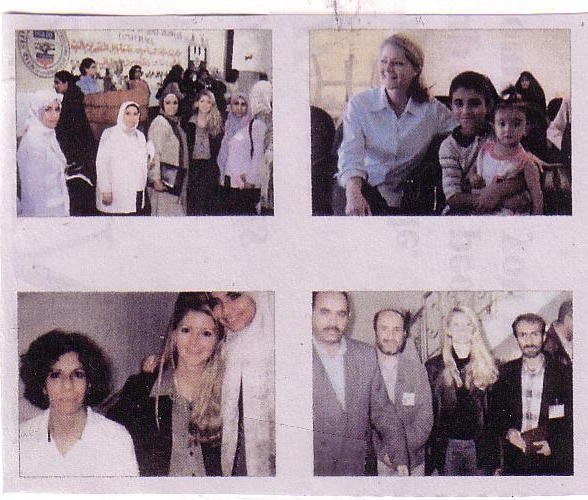

Although Holland went to Iraq for USAID, she later joined the Coalition Provisional Authority when it assumed the goal of opening Iraqi women's centers in every province.

Werchick said the centers were places women could organize, learn political skills to participate in a democracy, and learn life skills. "That was Fern's real passion. She worked on all of that. She'd say, "Can we get them sewing machines?" She'd just listen and figure out what the big priorities were."

"I've met so many wonderful people. So many of the women I've met are depending on me, and I'm going to see this through," Holland wrote to Green in an e-mail.

"She literally laid her life on the line for what she believed in, which was basic human rights and the rule of law," Green said. "Fern embodies everything that is noble about the practice of law. There are plenty of things that are not."

Governor Brad Henry posthumousley named Fern a

Heroic Oklahoman on Tuesday, April 6, 2004. "Fern Holland devoted

her life to helping people who needed it most, and she ultimately lost

her life because of that utter selflessness," Henry said. "Fern

Holland was an extraordinary person with an extraordinary love for humanity.

Her life is a source of inspiration for all of us to follow."

Fern was living proof, you don't have to wear a uniform and bear arms, to be a Hometown Hero. She had her beliefs and dreams, and wasn't afraid to work to achieve them. This beautiful and amazing woman could be a positive role model to young and old alike!

FERN HOLLAND CHARITABLE FOUNDATION

Family members and friends have set up the Fern Holland Charitable Foundation, which promotes human rights in Iraq and around the world

TO DONATE: Send checks to Suite 3700, 15 E. 5th Street, Tulsa, OK 74103.

We extend our heartfelt sympathy to Fern's family and friends, and we share their pride in this Oklahoma Hometown Hero.

PHOTO GALLERY

SENIOR YEAR AT MIAMI HIGH SCHOOL

|

|