For the first time all information printed in one book. Names of Civilians, Officers and Enlisted men taken from Government Records. Eight months of research - two years in the works to publish. 272 Pages of Information Packed into one Volume.

Why things happened as they did in the Chickasaw Nation after the Civil War.

The Arbuckle Historical Society is a registered non-profit organization under Internal Revenue Service Code 501(C) 3 regulations. 100% of the proceeds over publishing cost and shipping are donated to the the Society Museums in Sulphur and Davis.

How to Order:

Just send a check, or money order in the amount of $20 to either of the following;

Arbuckle Historical Society, 12 Main Street, Davis, OK 73030, (580) 369-2518

Arbuckle Historical Society, 402 W. Muskogee, Sulphur, OK, 73086 (580) 622-5593,

ORgo to Amazon.com, click on "books" and enter " Ft. Arbuckle " in the search window.

This is your total cost for the book, tax, shipping and handling. Posted January 10, 2005

|

The Story of Ft. Arbuckle, I.T. |

|

1851 - 1870 |

|

Preface Indian Territory, the land that became known as Oklahoma, was settled in the 1820's and 1830's by many of the tribes of Indians from east of the Mississippi River. There were many tribes that were forced or voluntarily moved to the new country. This influx of many new peoples created conflict with the indigenous peoples that before now occupied the land. Those indigenous people were made up of tribes such as the Arapaho, Kiowa, Cheyenne, Comanche, Osage, Kickapoo, Wichita and Caddo among others. The conflicts were predictable at best and were murderous at worse. The battles between the wild plains Indians and the newly arrived civilized Indians of the southeastern United States were immediate. The newcomers were ranchers and farmers who cultivated the land rather than hunters as were the plains Indians. The newcomers built houses and barns and raised livestock where the plains Indians moved to summer and winter hunting grounds. The plains Indians moved with the great herds of buffalo which provided their food clothing and shelter. The newcomers were seen as the ending of the great herds grazing areas and an impediment to their way of life. The new farmers and ranchers also provided a new source for horses, mules, cattle and crops to steal. One of the things to remember about tribes such as the Comanche and Kiowa were that they looked at their depredations totally different than that of the civilized tribes or the white man. The Comanche and Kiowa were of the mindset that all these things were for the taking. To the victor goes the spoils. A doctor goes to the hospital and heals the sick. A teacher goes to school and educates the unlearned. The Comanche goes to work and steals ponies and kills the enemy. It is that simple. This idea is where the point of contention of the United States Army, the plains tribes and civilized tribes came about. As early as the 1820's, the United States Army established post in the new country to protect these newly arrived tribes from the indigenous tribes and preserve some semblance of law and order on the new frontier. This was the purpose of Ft. Arbuckle and the other early post established in the west. |

The History of Fort Arbuckle

Chapter 1

The Newcomers

Indian Territory, the land that became known as Oklahoma, was settled in the

1820's and 1830's by many of the tribes of Indians from east of the Mississippi

River and north and east of Kansas. There were many tribes that were forced or

voluntarily moved to this new country.

This influx of new tribes created conflict with the indigenous peoples

that before now occupied this land.

These indigenous peoples were made up of tribes such as the Arapaho, Kiowa,

Cheyenne, Comanche, Osage, Kickapoo, Apache and Wichita among others.

The conflicts were predictable at best and were murderous at worse.

The battles between the wild plains Indians and the newly arrived

civilized Indians of the southeastern United States such as the Chickasaw,

Choctaw, Creek, Cherokee and Seminole were immediate.

The newcomers were ranchers and farmers who cultivated the land rather

than being hunters as were the plains Indians.

The newcomers built houses and barns and raised livestock or planted

crops where the plains Indians moved to summer and winter hunting grounds.

The plains Indians moved with the great herds of buffalo, which provided

their food, clothing and shelter.

The newcomers were seen as the end of the great herds grazing areas and an

impediment to their way of life. The

new farmers and ranchers also provided a new source for horses, mules, cattle

and crops to steal.

One of the things to remember about the wild plains tribes was that they looked

upon their depredations totally different than that of the civilized tribes or

the white man. They were of the mindset that all these things were for the

taking. To the victor goes the

spoils. A doctor goes to the

hospital and heals the sick. A

teacher goes to school and educates the unlearned.

The wild tribes go to work, steal ponies and kills the enemy.

It is that simple. It does

not require a degree in sociology to understand.

This idea is where the point of contention between the United States

Army, the plains tribes and civilized tribes came about.

As

early as the 1820's, (Ft. Gibson, 1824), the United States Army established

posts in the new country to protect these newly arrived tribes from the

indigenous tribes and preserve some semblance of law and order on the new

frontier. This was the purpose of

Ft. Arbuckle and the other early post established in the west.

There has actually been three different Army post in Indian Territory known as

Ft. Arbuckle. The first post was

located ( Lat. 34.50 North - Long 18.16 West) in what is now Creek County,

Oklahoma. It was a temporary camp

located at the confluence of the Cimarron River (Red Fork) and the Arkansas

River. The post was 70 miles

northwest of Ft. Gibson just a few miles west of present day Tulsa, OK.

Established on June 24th, 1834, the

post was abandoned on November 11, 1834.

It was assumed that a post in this area would be a show of force to the

Osage Indians that resided in this area.

Companies E and G of the 7th U.S. Infantry under the command of Major

George Birch and under the orders of General Leavenworth established the post.

The post was named after Col. Matthew Arbuckle of the 7th U.S. Infantry.

Through some misinterpretation of orders, the post was deemed to far

advanced in the Indian Territory and the maintenance and supply was determined

too great. Almost immediately there

was a recall to remove the troops from the garrison with the troops being

recalled to Ft. Gibson. Before the

recall was issued, there was a blockhouse built, the area and grounds were

cleared along with dirt work for defensive positions dug.

The post became known as Old Ft. Arbuckle.

The second Ft. Arbuckle was known as Camp Arbuckle to keep it from being

confused with Old Ft. Arbuckle.

Following orders, on August 22, 1850, Capt. Randolph Barnes Marcy with Company D

of the 5th U.S. Infantry, consisting of

4 officers and 48 enlisted men established the post on the Canadian River

( 34.50 Lat - 20.20 Long) one mile west of present day location of Byars, OK.

The purpose of this post was to protect the California Road and the

influx of immigrants going to the California gold fields as well as protection

against the raiding wild plains Indians.

Store houses and log barracks with puncheon floors were built.

The post was set for the winter as they were under roof by December 1st,

1850.

Captain Marcy received notice from the War Department that the post was not far

enough west and that he would have to find a more suitable location further west

and south along the Washita River.

Company D, 5th U.S. Infantry, spent the remainder of the winter at Camp Arbuckle

and proceeded to find a new location for the post the next spring.

On April 17th, 1851, the camp was abandoned and the garrison moved out to

find the new location of the post which is located 7 miles west of the present

town of Davis, OK.

Most of the garrison at Camp Arbuckle was struck with malaria during their stay.

The location of the new post was determined to be best situated on a hill

several miles from any river. Lt.

Rodney Glisan, Assistant Surgeon, was sent ahead with the orders to find a

"healthful and sanitary" location for the post.

Such a place was determined to exist about a mile south of Wildhorse

Creek. An ever-flowing spring of

water on a hill was found along with plenty of timber and building materials

close by. This location was chosen

and the third Ft. Arbuckle came into existence on April 19, 1851.

When Capt. Marcy and the garrison moved to the new location, Black Beaver, the

famous scout and chief of a band of Delaware occupied the buildings at Camp

Arbuckle. There were about 500

Delaware that moved to Camp Arbuckle at this time.

General Order #34 officially named the new post Ft. Arbuckle on June 25th, 1851.

Fort Arbuckle was garrisoned until February 13, 1858 when in accordance

to General Order #1, Headquarters of the Army, dated January 8, 1858, it was

abandoned. The troops of the 7th

U.S. Infantry at Forts Arbuckle, Smith and Washita were sent to Utah to fight in

the Mormon War. Company E, 1st U.S.

Infantry under command of Lt. James E. Powell,

pursuant to Special Order #39, Department of Texas, re-occupied the post

on June 29, 1858 and it remained a U.S. installation until May 5, 1861, when

on May 6, 1861, Texas troops seized the abandoned fort on behalf of the

Confederacy until the end of the Civil War.

U.S. Troops again occupied it on November 18, 1866, but finally abandoned

the fort on June 24, 1870, pursuant to Special Order 113, Department of the

Missouri, of that year. This is the

story of the turbulent twenty years of the post life and the people that built

and manned the garrison.

Chapter 2

The New Army Post

The five months that Company D, 5th Infantry spent at Camp Arbuckle passed quickly. On January 9th, 1851, Captain Marcy, a small detachment of troops and a few Creek

scouts started out to locate the new post. They journeyed south through the Arbuckle

Mountains exploring the rolling prairies, then south to the Red River. Then west on the

Red River to the mouth of Cache Creek. From here they trekked back to Camp Arbuckle,

a distance of 330 miles. When Marcy arrived back at camp he found new orders as to

where the post should be established. General Arbuckle ordered (General Order #44 -

1850) that the post should be near the Washita Crossing near the mouth of Wildhorse

Creek and near the Arbuckle Mountains. Within three weeks a road had been built

between Camp Arbuckle and the new post. Lt Myers was in charge of this part of the

operation. Upon reaching the site of the new post, Lt. Myers ordered the area cleared anda ga rden was planted.

This garden was the workings of Dr. Glisan who noticed that the lack of fresh vegetables

caused sickness in the troops. He knew that too much meat and no fruit or vegetables

cause various diseases and advocated that all military garrisons have a garden for fresh

greens. Dr. Glisan must have been years ahead of his time. Although he did not know the

reason, he recognized that being near water was a cause for malaria. He knew nothing of

the mosquito being a carrier. He also recognized that a nearly all meat diet caused scurvy

and other diseases. He thought a good diet of green vegetables and fruit would do much

for a healthy trooper.

During this time, Captain Marcy and his wife Mary departed for Ft. Washita where Mary

would stay while Ft. Arbuckle was constructed. Mary Marcy visited her old friends Mrs.

Ruggles and Mrs. Whitall and decided to stay with Mrs. Ruggles since she felt that she

had imposed on Mrs. Whitall enough.

The Marcy's then traveled back to Camp Arbuckle to pack and make ready to move. While there, a Delaware trader brought in a young Negro girl about 15 years old who was

horribly mutilated and scarred. She was gaunt with sunken cheeks and dressed in barely

enough ragged clothes to cover her. She had been a part of the runaway slaves that

followed the Seminole chief Wild Cat to the Rio Grand. Her party had been captured by

the Comanche who performed "medical experiments" on her. The Comanche had never

seen a black person before and knew nothing about them. Mrs. Marcy took the young girl

to the kitchen and fed her. She then made a bed for the girl to rest for a while. She later

recounted that the Comanche had taken a knife and scraped and cut through the skin to

see if it was black like the exterior. They then burned her with live coals to see if she

experienced pain as they did. On April 17th, 1851, the garrison struck camp for the last

time and made the two day march to the new post arriving on April 19, 1851.

For future reference, the term "Post Returns" means the monthly reports sent back to the army command from the outlying posts. This volume is relying heavily on the post returns

from the National Archives. These Returns listed every person who was employed or was

serving in the army. They listed the names and rank of the officers as well as that of the

enlisted men. Also listed were the civilian employees such as teamsters, wheelwrights,

blacksmiths, carpenters, masons, scouts, etc. with rates of pay. Additionally, on these

Returns were the orders received that month and any other information deemed necessary

for those in command.

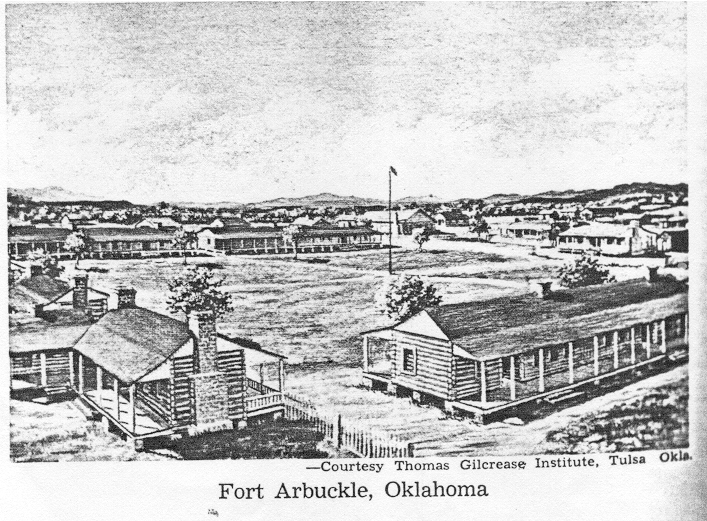

Lt. Rodney Glisan, the post surgeon, in his book "A Journal of Army Life", 1874, reported

that as of May 12th, 1851, the garrison was living in tents. "The carpenters and extra duty

men were engaged in erecting the enlisted men's barracks which will be built of hewn logs,

with chinks stopped with small pieces of wood and clay loam. The floors will be of

puncheons and the roof will be clapboards. The buildings will be arranged into an oblong

rectangular parallelogram with a line of barracks on each side for the men - the

commissary and quartermaster buildings at one end and the officers quarters at the other.

The hospital which will be erected as soon as the private soldiers are under cover., will be

a long one story building divided into four compartments - one of which will be used as a

dispensary with the steward's room adjoining - the next two as wards for the sick - and the

fourth as a kitchen. This building will be erected a short distance outside the garrison.

The sutler's store is about a hundred yards north of the commissary buildings. Just under

the brow of the hill is a limpid spring of icy water gushing forth in a stream powerful

enough to run a first class mill." Lt. Glisan, who was a tee-totaler, lamented that it was

too bad that the men were not content with this wholesome beverage. It troubled the

young doctor that the men, who were compelled to uphold the law against bringing spirits

into the Indian country were themselves the cause of much of it's illicit sale.

This point is where much contention about the size of Ft. Arbuckle came about. As it

was a federal offense to sell spirituous liquor on a military reservation, it was decided to

make the reservation so large that it would be impractical for a soldier to travel a days

journey in the dark of night to retrieve the illicit brew. It was first decided that the military

reservation would be seven miles in every direction from the main post. That would be a

staggering fourteen by fourteen miles or one hundred ninety six square miles. This drew

the consternation of the Choctaw and Chickasaw people. Many of the local residents

suddenly found themselves inside a military reservation. The army's point of view was

simply that if they behaved themselves, the local citizens had nothing to fear from the

army.

The Treaty of 1855 brought the problem to a head. The Chickasaw were living in the

Choctaw country and were slowly being absorbed into the Choctaw culture. Although the

Chickasaw paid $150,000 for the right to live in the Choctaw Nation, they were not

allowed a defined boundary or nation of their own. The Chickasaw were an autonomous

nation but the customs and beliefs of the Choctaw were slowly eroding the Chickasaw

culture. In 1854, a treaty was began to create a new nation with defined boundaries

carved out of the Choctaw Nation. Article 17 of that treaty later became a thorn in the

flesh for the U.S. Army. The section of the treaty reads as follows:

ARTICLE 17. The United States shall have the right to establish and maintain such

military posts, post-roads, and Indian agencies, as may be deemed necessary within the

Choctaw and Chickasaw country, but no greater quantity of land or timber shall be used

for said purposes, than shall be actually requisite; and if, in the establishment or

maintenance of such posts, post-roads, and agencies, the property of any Choctaw or

Chickasaw shall be taken, injured, or destroyed, just and adequate compensation shall be

made by the United States. Only such persons as are, or may be in the employment of the

United States, or subject to the jurisdiction and laws of the Choctaws, or Chickasaws,

shall be permitted to farm or raise stock within the limits of any of said military posts or

Indian agencies. And no offender against the laws of either of said tribes, shall be

permitted to take refuge therein.

The interpretation of the last two sentences of this article means that no person who is

white may live inside the reservation. It also means that no person who is not Chickasaw

or Choctaw or married to a member of these two tribes may live, farm or raise stock in the

military reservation. This does not include intermarried whites who became citizens of the

respective tribe. White employees of the Army could live inside the military reservation.

This would be people such a s scouts, interpreters, masons, carpenters and sutler's. No

person may live inside the reservation who has committed a crime against a member or

Nation of the Chickasaw or Choctaw Nations. This eliminated a lot of people.

The part of this article that referred to "no greater land than necessary" would haunt the

army for years. The army and War Department began to receive the complaints from the

civilians that had land consumed by the new post. Indian Agent Douglas Cooper and

Governor Cyrus Harris of the Chickasaw Nation began a campaign to get the size of the

post reduced. The citizens of the area included Smith Paul who later founded the town of

Pauls Valley and William Muncrief a relative of this writer. The solution of this problem

will be addressed later.

In a letter dated October 12th, 1854, Major George Andrews Commanding, wrote to

Major Page of the Adj. Gen. Office at Jefferson Barracks, MO that there must be a survey

made of Ft. Arbuckle as there was much confusion with the influx of settlers and those

wanting to do business with the army. Many applications were made to Ft. Arbuckle for

permission to locate in the vicinity but there was no one who knew exactly where the

military reservation boundary was located. In June, 1851, Major Andrews assumed

command from Cap. Marcy who was ordered to build a military road to Texas and

establish a string of forts in the Comanche country of west Texas. Major Andrews was

verbally given orders by General Arbuckle as to the size and composition of the military

reserve. General Arbuckle was now dead and there were no written record of the

General's intentions.

Capt. Marcy had declared the reserve to be seven miles in all directions from the main fort. However General Arbuckle in his verbal orders to Major Andrews stated that he wanted

the post to be " Seven miles east, five north, south and west until fixed by proper

authority". The post was now reduced to 120 square miles down from the 196 square

miles that Marcy first directed. These limits included the best timber for building the post,

command the best and nearest crossing of the Washita River, the best water and grass for

the stock. No survey of the post had ever been made of the post since Major Andrews

had taken command of the post in June,1851.

Captain Marcy had been ordered south to Texas to build a string of forts through the

Comanche country and had taken 200 odd men from the garrison at Ft. Arbuckle by order

of the War Department. This left the few remaining men to complete the post. This

overwork and constant fatigue prevented the post commander from doing the survey

himself. Major Andrews felt that his recommended size of the post allowed for the best

use of the raw materials for construction of the post especially the limestone and timber. He also felt that there was a sufficient amount of coal in the area for fuel. There was

indeed a minor deposit of coal but it was so small as not to be feasible to recover.

The Treaty of 1855 between the Choctaw and Chickasaw and the U.S. Government came

and passed and still no survey of the military reservation had been made in four years. In a

letter to Commissioner J.W. Denver dated Nov. 1st, 1857, Indian Agent D. H. Cooper

stated that he had visited Ft. Arbuckle and saw that the size of the reserve was now fixed

at ten miles by twelve miles or 120 square miles. Cooper stated simply that "it is bigger

than it ought to be". Cooper wanted to establish an agency near the fort for the

Chickasaw and Choctaw and offered to plat it for the army and furnish a plat for them. Cooper wanted the reserve to be cut down to a limit of "two miles east and three miles

west, two miles south and three miles north". Agent Cooper wanted the post trimmed

down to a size of five by five miles for a total of twenty five square miles. Cooper ends

his letter by stating that the land immediately west of the post is the most desirable in the

entire Choctaw and Chickasaw Nation. This is the same area where Smith Paul, a white

man married to a Choctaw woman, had his ranch and it is wondered how much political

influence was exerted on Agent Cooper by Paul to get the army to reduce the size of the

reserve. It was not until 1859 when Lt. Whipple, U.S. Army surveyor, finally surveyed

and platted the post and put markers along the post boundary. The reason for the need of

having the post so far east was to include the rock bottom crossing of the Washita River. This put the present town of Davis, OK inside the post perimeter. By 1869, one year

before de-activation, the size of the post had been reduced to one mile square.

Chapter 3

Building the New Post

The new post was situated on the north edge of the Arbuckles Mountains. In Dr. Glisan's

memoirs, he referred several times to what we call today the Arbuckles as the Washita

Mountains. It could have been that before the post was built, that was the name the locals

used to refer to these ancient hills. This writer has never heard this name used before in

any other volume. It is indeed curious that a person who was there at the time the post

was erected would call the mountains "the Washitas". The young doctor was entranced

with the area and it's beauty. He made many rides into the mountains and described

exactly how the rows of stone uplifts looked like tombstones.

While the soldiers worked to build the post, they did have help from civilian builders. In

the post returns, it is mentioned that along with the soldiers there were carpenters and

masons employed by the army. These artisans were paid the sum of $2.50 per day and

one ration.

Most of the information that is known about the actual building of the fort is from the

post returns and the journal of Dr. Glisan. The young doctor was more than the post

surgeon. He was a ardent observer of the natural beauty of the Arbuckle Mountains. He

kept a journal of the plants and animals of the area as well as descriptions of the land. The

good doctor also kept meticulous records of the weather recording temperature, rainfall,

tornadoes, lightning storms and floods.

Chapter 10

The Cemetery at Ft. Arbuckle

On

August 6, 1872, William W. Belknap, Secretary of War, gave instructions to have

the remains of his father, General William Goldsmith Belknap, removed from Fort

Washita, where he was interred in 1851, to the cemetery at Keokuk, Iowa, the

home of the Secretary. At the same time he directed the quartermaster general to

arrange for the removal of the remains of other soldiers and their families

found at Fort Washita, Fort Towson and Fort Arbuckle, to the National Cemetery

at Fort Gibson.

Bids were advertised for, and a contract let to P. J.

Byrne of Fort Gibson, who succeeded in removing the remains of forty-six persons

in 1872: only two of them, however, were definitely known to be soldiers. Owing

to the careless manner in which the men who served at the remote post had been

buried, and the fact that fires had been permitted to run through the cemeteries

and burn off all wooden headboards, and the difficulty of finding other marks of

identification in the graves, or indeed, of finding the remains and the boxes

containing them in such condition that they could be removed at all,

instructions were given to abandon further removal. However, information was

later acquired of forty-six additional graves at Fort Washita; fifty-four at

Fort Arbuckle, and eighteen at Big Sandy Creek (today known as Guy Sandy Creek)

on the Fort Smith and Fort Arbuckle road. Efforts were then renewed, and another

contractor undertook to remove the remains to the Fort Gibson National Cemetery

but this effort was not successful.

The removal of remains from

all these burial places was attended with much difficulty because of the lack of

identifying marks. It was impossible to determine whether they were removing

soldiers or civilians, and the whole undertaking was attended with much

confusion. It appeared that during the Civil War a large number of Confederates

died and were buried near Fort Washita. The correspondence relating to the

subject would indicate that removal of the dead from this cemetery was limited

to those known to have been in the service of the Union Army, and the

Confederate dead were probably not disturbed.

In a report dated December 31,

1893, which accounted for graves in the National Cemetery at Fort Gibson, of 231

known to be soldiers and 2,212 whose identity and service were unknown. Of the

relatively few who are identified by inscriptions on monuments, the greatest

number are to be seen within what is known as the Officers' Circle. Among these

is Flora, the young Cherokee wife of Lieutenant Daniel H. Rucker, who died at

Fort Gibson June 26, 1845. Her husband survived her to become in later years

Quartermaster General of the United States Army. John Decatur, brother of

Stephen Decatur, died on November 12, 1832, while a settler at Fort Gibson.

Lieutenant John W. Murray of the West Point Class of 1830, of the Seventh

Infantry, was killed on February 14, 1831, by being thrown from his horse.

Murray's classmate, Lieutenant James West, died at Fort Gibson on September 28,

1834. There were many people buried in the Ft. Arbuckle cemetery that were not

military. Many of these were captured by the Comanche and Kiowa. Often the

identities of those interred here were never know. Below is a list of those

who's identities are known.

|

Ft. Arbuckle's Lasting Legacy |

|

Chapter 11 |

|

|

Research book notes:

Cannons at ft sill from ft arbuckle

| 24-pounder iron flank howitzers, Model of 1844 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alger | *JWR | 47 | QM Whse, from Ft. Arbuckle IT | ||||

| Alger | *JWR | 49 | QM Whse, from Ft. Arbuckle IT | ||||

| Alger | *JWR | 49 | storage, from Ft. Arbuckle IT | ||||

| Alger | *JWR | 49 | storage, from Ft. Arbuckle IT | ||||

| Alger | *JWR | 49 | storage, from Ft. Arbuckle IT | ||||

|

Scanland's Texas Cavalry Battalion |

| July 3, 1862 | Attached, District of the Indian Territory, Trans-Mississippi Department |

| April 30, 1863 | Cooper's Brigade, Steele's Division, District of the Indian Territory, Trans-Mississippi Department |

| Jan.1, 1864 | First Brigade, District of the Indian Territory, Trans-Mississippi Department |

Even though the unit served attached to commands in the Indian Territory during its entire career, the unit participated in engagements in Arkansas as well as in the Territory. Listed below are the specific engagements in which Scanland's Texas Cavalry Battalion participated.

| Battle, Prairie Grove, Fayetteville (Illinois Creek), Arkansas | Dec. 7, 1862 |

| Operations against the Expedition over the Boston Mountains, Arkansas | Dec. 27-29, 1862 |

| Skirmish, Dripping Springs, and Capture, Van Buren, Arkansas | Dec. 28, 1862 |

| Skirmish, Cherokee County, Indian Territory | January 18, 1863 |

| Action near Fort Gibson, Indian Territory | May 25, 1863 |

| Skirmish, Fort Gibson, Indian Territory | May 28, 1863 |

| Skirmish, Greenleaf Prairie, Indian Territory | June 16, 1863 |

| Engagement, Cabin Creek, Indian Territory | July 1-2, 1863 |

| Engagement, Elk Creek near Honey Springs, Indian Territory | July 17, 1863 |

| Action, Perryville, Indian Territory | Aug. 26, 1863 |

| Operations in the Cherokee Nation, Indian Territory | Sept. 11-25, 1863 |

| Operations in the Indian Territory | Feb. 1-21, 1864 |

July-November, 1868: Company at Ft. Arbuckle, I.T.; The company was busy during this period drilling, repairing buildings, and chasing cattle rustlers, and bootleggers. Mail delivery was especially dangerous. Murdering thieves so often attacked mail carriers, that only Indians, and soldiers dared to carry it. Private Filmore Roberts of the Tenth, showing great courage in an attempt to deliver the mail, drowned crossing the Northern Canadian River.

November 1868: Company at Fort Arbuckle, I.T.: In a show of force, Lieutenant Gray leads the entire company to Eureka Valley.

December, 1868: Company at Fort Cobb, Indian Territory; On December 1, 1868 the Company marched 96 miles from Fort Arbuckle to Fort Cobb, I.T. It remained at Fort Cobb until December 27th when it marched 60 miles to Medicine Bluff Creek, and then returned to Fort Cobb.

Ft. Gibson burials from Ft. Arbuckle

BUTLER, John Pvt. Mar 29, 1868 Fort

Arbuckle

NEVILLE, John Pvt. Oct 12, 1869 Fort

Arbuckle

CLACKIN, Wm. Sgt. Oct 11, 1867 Fort

Arbuckle

TAYLOR, Samuel Pvt. July 7, 1867 Fort

Arbuckle

WHEELER, H. Pvt. Apr 22, 1868 Fort

Arbuckle

POWELL, William Citizen - - Fort

Arbuckle

CAMPBELL, Jim G. Civilian Apr 24, 1860 Fort

Arbuckle

ELIOT, J. H. Major Nov 27, 1868 Fort

Arbuckle

CARROLL, M. L. Pvt. Nov 24, 1858 Fort

Arbuckle

DORSEY, James Pvt. - - Fort

Arbuckle

ROBENT, John Pvt. Apr 28, 1876 Fort

Arbuckle

SEARLES, James Pvt. Sept 6, 1868 Fort

Arbuckle

REVES, Joseph Pvt. 1872 Fort

Arbuckle

Research book note #2:

As for Fort Arbuckle, the midwife so to speak, its days were numbered. Three years after the 2,300 longhorns passed by, the fort was abandoned. Fort Sill had been established farther west, and the troops were transferred there.

All that remains of Fort Arbuckle today is a chimney from the officers' quarters, now part of a home built there later. A flagpole stands on the old parade grounds, and an old historical marker is partially obscured on State Highway 7 nearby.

In the early 1700s, the Wichita were a Southern confederacy of Caddoan tribes along the Arkansas River in Oklahoma and along the Red and Brazos Rivers in Texas. By the 1850s, they lived around the Wichita Mountains of southwestern Oklahoma and later, along Rush Creek in Grady County. The Rush Creek site is where the tragic Battle of the Wichita Village took place: In 1858, parts of the Second U.S. Cavalry (tracking Comanche raiders fleeing from Texas) mistakenly attacked. Their village destroyed, they took refuge at Ft. Arbuckle.

Edward S. Hayes Service, Indian Wars and Civil War, Pvt., 4th U.S. Cav.; First Lt., Co. H, 1st Ind. Cav.; and Second Lt. 144th Ind. Inf. Edward enlisted in March 1855 as a Private Company D, Fourth U.S. Cavalry and was sent into rendezvous at Jefferson Barracks near St. Louis. In June 1855, the Regiment went to Ft. Leavenworth, remaining until September when it pursued the Sioux. In 1856, the Regiment was involved in border skirmishes in Kansas. In 1857, he was involved in an expedition against the Cheyenne. In spring 1858, the Regiment started for Utah to take action concerning the Mormons, but a compromise was reached, and the Regiment instead went to Indian Territory to engage the Comanches. The Regiment remained at Ft. Arbuckle until the summer of 1869, when it was sent to the Wichita Mountains to build a post.

29th Texas Cavalry impression. Plans are to make it a thoroughly documented site-specific study of this one unit throughout their experience in the war (they began by fighting plains Indians and Unionist dissentors on the frontier of Texas, then did Indian duty at Ft. Arbuckle in South-central OK, then joined Cooper's CS command in the Indiant Territory, where they remained a part of the force there for the rest of the war.

May 4

Fort Arbuckle, Indian Territory is evacuated

by Federal forces.